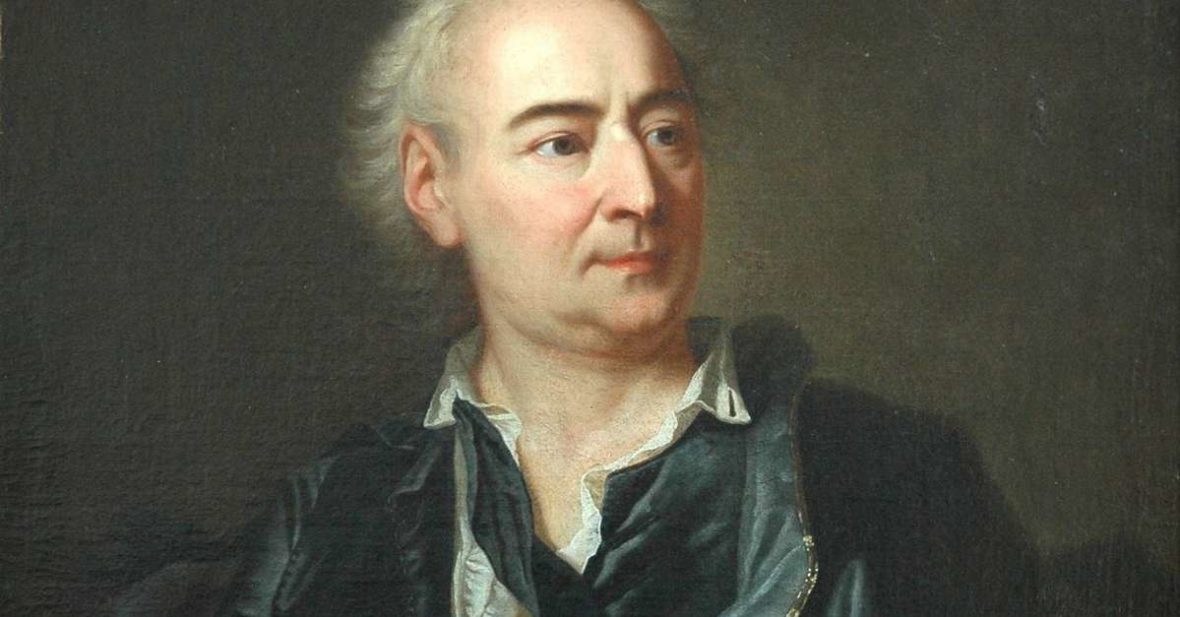

Denis Diderot was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the Encyclopedie along with Jean le Rond d’Alembert. He was a prominent figure during the Enlightenment. Take a look below for 40 more fascinating and interesting facts about Denis Diderot.

1. Diderot was born in Langres, Champagne.

2. His parents were Didier Diderot (1685–1759), a cutler, maître coutelier, and Angélique Vigneron (1677–1748).

3. Three of five siblings survived to adulthood, Denise Diderot (1715–1797) and their youngest brother Pierre-Didier Diderot (1722–1787), and finally their sister Angélique Diderot (1720–1749).

4. According to Arthur McCandless Wilson, Denis Diderot greatly admired his sister Denise, sometimes referring to her as “a female Socrates”.

5. Diderot began his formal education at a Jesuit college in Langres, earning a Master of Arts degree in philosophy in 1732.

6. He then entered the Collège d’Harcourt of the University of Paris.

7. He abandoned the idea of entering the clergy in 1735, and instead decided to study at the Paris Law Faculty.

8. His study of law was short-lived however and in the early 1740s, he decided to become a writer and translator.

9. Because of his refusal to enter one of the learned professions, he was disowned by his father, and for the next ten years he lived a bohemian existence.

10. In 1742, he befriended Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whom he met while watching games of chess and drinking coffee at the Café de la Régence.

11. In 1743, he further alienated his father by marrying Antoinette Champion (1710–1796), a devout Roman Catholic.

12. The match was considered inappropriate due to Champion’s low social standing, poor education, fatherless status, and lack of a dowry. She was about three years older than Diderot.

13. The marriage, in October 1743, produced one surviving child, a girl. Her name was Angélique, named after both Diderot’s dead mother and sister.

14. The death of his sister, a nun, in her convent may have affected Diderot’s opinion of religion.

15. She is assumed to have been the inspiration for his novel about a nun, La Religieuse, in which he depicts a woman who is forced to enter a convent where she suffers at the hands of the other nuns in the community.

16. Diderot had affairs with Mlle. Babuti, Madeleine de Puisieux, Sophie Volland and Mme de Maux.

17. His letters to Sophie Volland are known for their candor and are regarded to be “among the literary treasures of the eighteenth century”.

18. In 1746, Diderot wrote his first original work: the Philosophical Thoughts.

19. Diderot’s most intimate friend was the philologist Friedrich Melchior Grimm.

20. They were brought together by their friend in common at that time, Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

21. In 1759, Grimm asked Diderot to report on the biennial art exhibitions in the Louvre for the Correspondance. Diderot reported on the Salons between 1759 and 1771 and again in 1775 and 1781.

22. Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805) was Diderot’s favorite contemporary artist.

23. Diderot appreciated Greuze’s sentimentality, and more particularly Greuze’s portrayals of his wife who had once been Diderot’s mistress.

24. When the Russian Empress Catherine the Great heard that Diderot was in need of money, she arranged to buy his library and appoint him caretaker of it until his death, at a salary of 1,000 livres per year. She even paid him 50 years salary in advance.

25. When returning, Diderot asked the Empress for 1,500 rubles as reimbursement for his trip. She gave him 3,000 rubles, an expensive ring, and an officer to escort him back to Paris.

26. He would write a eulogy in her honor on reaching Paris.

27. In 1766, when Catherine heard that Diderot had not received his annual fee for editing the Encyclopédie (an important source of income for the philosopher), she arranged for him to receive a massive sum of 50,000 livres as an advance for his services as her librarian.

28. In July 1784, upon hearing that Diderot was in poor health, Catherine arranged for him to move into a luxurious suite in the Rue de Richelieu. Diderot died two weeks after moving there—on 31 July 1784.

29. In his youth, Diderot was originally a follower of Voltaire and his deist Anglomanie, but gradually moved away from this line of thought towards materialism and atheism, a move which was finally realized in 1747 in the philosophical debate in the second part of his The Skeptic’s Walk (1747).

30. In his 1754 book On the interpretation of Nature, Diderot expounded on his views about Nature, evolution, materialism, mathematics, and experimental science.

31. It is speculated that Diderot may have contributed to his friend Baron d’Holbach’s 1770 book The System of Nature.

32. Diderot died of pulmonary thrombosis in Paris on 31 July 1784, and was buried in the city’s Église Saint-Roch.

33. His heirs sent his vast library to Catherine II, who had it deposited at the National Library of Russia.

34. He has several times been denied burial in the Panthéon with other French notables.

35. The French government considered memorializing him in this fashion on the 300th anniversary of his birth, but this did not come to pass.

36. Otis Fellows and Norman Torrey have described Diderot as “the most interesting and provocative figure of the French eighteenth century.”

37. In 2013, the tricentennial of Diderot’s birth, his hometown of Langres held a series of events in his honor and produced an audio tour of the town highlighting places that were part of Diderot’s past, including the remains of the convent where his sister Angélique took her vows.

38. On 6 October 2013, a museum of the Enlightenment focusing on Diderot’s contributions to the movement, the Maison des Lumières Denis Diderot, was inaugurated in Langres.

39. French author Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt wrote a play titled Le Libertin which imagines a day in Diderot’s life including a fictional sitting for a woman painter which becomes sexually charged but is interrupted by the demands of editing the Encyclopédie.

40. In 1993, American writer Cathleen Schine published Rameau’s Niece, a satire of academic life in New York that took as its premise a woman’s research into an (imagined) 18th-century pornographic parody of Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew.