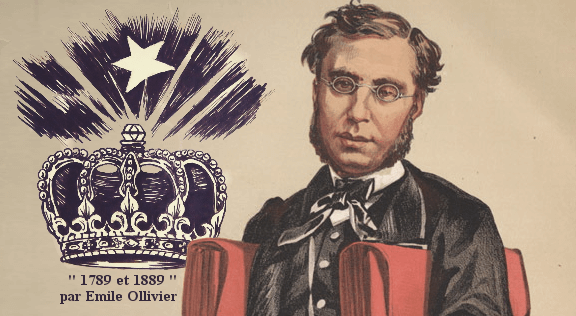

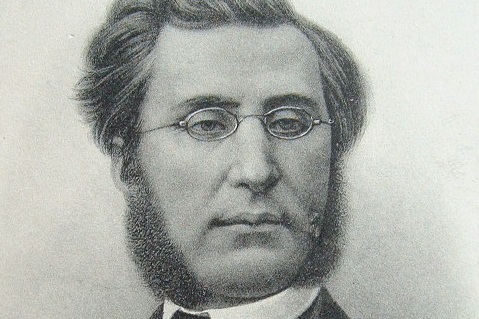

Olivier Emile Ollivier was a French statesman. Starting as an avid republican opposed to Emperor Napoleon III, he pushed the Emperor toward liberal reforms and in turn came increasingly into Napoleon’s grip. He entered the cabinet and was the prime minister when Napoleon fell. Take a look below for 27 more awesome and interesting facts about Emile Ollivier.

1. Ollivier was born in Marseille.

2. His father, Démosthène Ollivier (1799–1884), was a vehement opponent of the July Monarchy, and was returned by Marseille to the Constituent Assembly in 1848 which established a republic.

3. The father’s opposition to Louis Napoleon led to his banishment after the coup d’état of December 1851, and he returned to France only in 1860.

4. With the establishment of the Second Republic, his father’s influence with Ledru-Rollin secured for Émile Ollivier the position of commissary-general of the département of Bouches-du-Rhône.

5. Ollivier, then twenty-three, had just been called to the Parisian bar.

6. Less radical in his political opinions than his father, he suppressed a socialist uprising at Marseille, commending himself to General Cavaignac, who made him prefect of the department.

7. He was shortly afterwards removed to the comparatively unimportant prefecture of Chaumont-la-Ville (Haute-Marne), a demotion perhaps brought about by his father’s enemies.

8. He resigned from the civil service to take up a practice at the bar, where his abilities assured his success.

9. He re-entered political life in 1857 as deputy for the 3rd circumscription of the Seine département.

10. His candidacy had been supported by the Siècle, and he joined the constitutional opposition.

11. With Alfred Darimon, Jules Favre, JL Hénon and Ernest Picard he formed a group known as Les Cinq (the Five), which wrung from Napoleon III some concessions in the direction of constitutional government.

12. Although still a republican, Ollivier was a moderate who was prepared to accept the Empire in return for civil liberties even if it was a step-by-step process.

13. The imperial decree of 24 November, permitting the insertion of parliamentary reports in the Moniteur, and an address from the Corps Législatif in reply to the speech from the throne, were welcomed by him as an initial piece of reform.

14. This marked a considerable change of attitude, for only a year previously he attacked the imperial government, in the course of a defence of Étienne Vacherot, brought to trial for the publication of La Démocratie. This resulted in his suspension from the bar for three months.

15. He gradually separated from his old associates, who grouped themselves around Jules Favre, and during the session of 1866–1867, Ollivier formed a third party, which supported the principle of a Liberal Empire.

16. On the last day of December 1866, Count AFJ Walewski, continuing negotiations begun by the duc de Morny, offered to make Ollivier the Minister of Education, representing the general policy of the government in the Chamber.

17. The imperial decree of 19 January 1867, together with the promise inserted in the Moniteur of a relaxation of the stringency of the press laws and of concessions in respect of the right of public meeting, failed to satisfy Ollivier’s demands, and he refused the office.

18. On the eve of the general election of 1869, he published a manifesto, Le 19 janvier, on his policy.

19. The sénatus-consulte of 8 September 1869 gave the two chambers ordinary parliamentary rights, and was followed by the dismissal of Eugène Rouher and the formation in the last week of that year of a ministry of which Ollivier was really premier, although that office was not nominally recognized by the constitution.

20. The revival of the candidature of Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen for the Spanish throne early in 1870 disconcerted Ollivier’s plans.

21. The French government, following Gramont’s advice, instructed their ambassador to Prussia, Benedetti, to demand from the Prussian king a formal disavowal of the Hohenzollern candidature.

22. Ollivier allowed himself to be won over by the war party.

23. It is unlikely that he could have prevented the eventual outbreak of war, maybe he might have postponed it if he had heard Benedetti’s account of the incident. He was outmaneuvered by Otto von Bismarck, and on 15 July he made a hasty declaration in the Chamber that the Prussian government had issued to the powers a note announcing the rebuff received by Benedetti, the Ems Dispatch.

24. He obtained a war vote of 500,000,000 francs, and said that he accepted the responsibility of the war “with a light heart,” saying that the war had been forced on France.

25. He had many connections with the literary and artistic world, being one of the early Parisian champions of Richard Wagner.

26. His first wife, Blandine Liszt, was the daughter of Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult.

27. Liszt died in 1862, and in September 1869 Ollivier married Marie-Thérèse Gravier, then 19 years old. They had three children.